This is a guest blogpost by Josiah Fiscus. Josiah Fiscus is a 31-year-old gamer from Pittsburgh, PA who has been playing CCGs and designer board games for over two decades. When he’s not at the game table, you’ll find him playing drums and serving as a deacon in his local church or enjoying time outdoors with his wife, Erin, and two kids (ages 5 and 3).

This article will primarily apply to constructed and draft formats. When playing a sealed format, you have little to no control over the actual contents of your deck, and this article deals with making choices about what your deck is trying to accomplish. Even so, knowing what cards are best used proactively and reactively will help you make better play decisions, even with a completely random deck.

Principle 1: All decks exist on a spectrum of Proactive to Reactive. In fact, all cards do as well. Some cards can be used proactively or reactively, but others are pretty clearly pigeonholed into one role or the other. Where a deck falls on this spectrum is going to be dictated by what cards are included in said deck. A deck full of reactive cards will necessarily be a reactive deck. But what exactly do these terms mean?

Principle 2: Proactive decks try to win, not to stop the opponent from winning. Raging T-Rex is a good example of a proactive card. If you imagine a deck consisting of just 30 Raging T-Rexes, the game plan is pretty clear: attack for damage every turn. This deck has no way to interact with what the opponent is doing and no capability to block attacks; it simply seeks to put out as much damage as possible. Now it should be noted that a proactive deck doesn’t necessarily have to be aggressive or contain lots of effects that deal damage to a player; a deck that simply seeks to win by drawing the entire deck as fast as possible would also be proactive. At the heart of it, a proactive deck is defined by its desire to present lots of threats and comparatively few answers to opposing threats.

Principle 2: Proactive decks try to win, not to stop the opponent from winning. Raging T-Rex is a good example of a proactive card. If you imagine a deck consisting of just 30 Raging T-Rexes, the game plan is pretty clear: attack for damage every turn. This deck has no way to interact with what the opponent is doing and no capability to block attacks; it simply seeks to put out as much damage as possible. Now it should be noted that a proactive deck doesn’t necessarily have to be aggressive or contain lots of effects that deal damage to a player; a deck that simply seeks to win by drawing the entire deck as fast as possible would also be proactive. At the heart of it, a proactive deck is defined by its desire to present lots of threats and comparatively few answers to opposing threats.

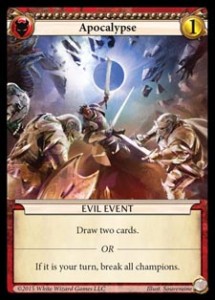

Principle 3: Reactive decks try to disrupt the opponent’s plans and win only when the opportunity presents itself. Apocalypse is a good example of a reactive card. At its best, you can use it to eliminate a lot of opposing threats at once, but you must be willing to do so even at the cost of eliminating your own threats on the board. A theoretical deck consisting of just 30 Apocalypses would only be able to win by the seldom-seen victory condition of trying to draw a card with an empty draw pile. So a reactive deck is the mirror of a proactive deck, instead seeking to present lots of answers and comparatively few threats.

Principle 3: Reactive decks try to disrupt the opponent’s plans and win only when the opportunity presents itself. Apocalypse is a good example of a reactive card. At its best, you can use it to eliminate a lot of opposing threats at once, but you must be willing to do so even at the cost of eliminating your own threats on the board. A theoretical deck consisting of just 30 Apocalypses would only be able to win by the seldom-seen victory condition of trying to draw a card with an empty draw pile. So a reactive deck is the mirror of a proactive deck, instead seeking to present lots of answers and comparatively few threats.

Principle 4: Many cards in Epic can serve either goal or both goals. Let’s consider Angel of Death. With the Loyalty trigger, this card is essentially an Apocalypse (reactive) strapped to an Airborne threat (proactive). As such, it is a very strong pick in draft as you will be glad to play it regardless of which direction your deck ends up going. Slightly weaker, but still strong, are cards like Flame Strike. This card too, will slot into either type of deck, but when you play it you will need to choose whether to be reactive (targeting an opposing Champion) or proactive (targeting your opponent). It’s also worth noting that card draw effects are not inherently proactive or reactive. Rather, they merely dig for other cards in your deck. So if the composition of your deck is more reactive, draw effects are more likely to find you reactive cards. Thus, card draw is a great draft choice if you feel that none of the other available cards help you further the goal of your deck. Similarly, during the game, card draw is a great thing to spend your gold on if none of the other cards in your hand help further your current plan.

Principle 5: A good deck can move seamlessly between these goals. You might have noticed that neither the 30 Apocalypse nor the 30 Raging T-Rex deck would be particularly competitive. Having some degree of balance is actually desirable in the decks you draft and construct. In a draft where I had chosen removal Events for my first few picks, I would be highly prioritizing taking a threat for my next pick, even if the available threats were of lower quality than the available answers. This idea of moving between these goals means that you want a deck in which the cards can occupy as much of the proactive-reactive spectrum as possible. You want to be able to answer the threat of a turn-one win from a proactive token deck as well as have enough threats to punish a slower, more controlling reactive deck. Most importantly, if you and your opponent are both playing very proactive decks, you need to be able to recognize when your opponent is able to be more proactive than you are. If you are going to lose the proactive race of dealing 30 damage first, you need to switch into reactive mode until you can stabilize. Bait your opponent into overextending, and once you have answered his/her threats, switch back to a proactive onslaught of your own. Knowing when to be reactive and when to be proactive is primarily a skill that can only be honed with practice.

Recent Comments